Click here for PDF version

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western Church

PART ONE

The Church struggles for survival

ROME, A.D. 64-----The capital of the world is in flames!

For six days and nights the great fire races out of control through the most populous districts of the imperial city. In its fury, the blaze reduces half the metropolis to ashes. Many of the architectural glories of ancient Rome are devoured in the flames. Thousands of terror-stricken Romans are made homeless, all their wordily possessions are lost.

From atop his palace roof, the Emperor Nero views the awesome panorama.

Some Romans suspect the truth. They believe that Nero----inhuman, maniacal, insane-----has personally triggered the conflagration. Fancying himself a great builder, he desires to erase the old Rome that he might have the glory of founding a new and grander city—Nero’s Rome!

A rumor begins to circulate that the fire was contrived by the emperor himself. Nero fears for his safety. He must find someone to bear the blame----and quickly.

To divert suspicion away from himself, Nero lays the guilt at the door of the new religious group----the Christians of Rome. It is the logical choice. Christians are already despised and distrusted by many. They spurn the worship of the old Roman gods and “treasonably” refuse to give divine honors to the emperor. Their preaching of a new King sounds like revolution

They have no influence, no power----the perfect scrape goats.

Nero orders their punishment. The bloodbath begins. The emperor inflicts on the falsely accused Christians horrible tortures and executions. Some are nailed to crosses; others are covered with animal skins and torn apart by wild dogs in the Circus Maximus; still others are nailed to stakes and set ablaze as illumination for Nero’s garden parties. For years the persecution rages. It is a perpetual open season on Christians Among those imprisoned and brought to trial by Nero is a man who has been instrumental in establishing the fledgling Church of God at Rome----Paul, the apostle to the Greek-speaking gentiles.

Apostolic Martyrs

For many years Paul had warned the churches of impending persecutions. He had reminded them of Jesus’ own words to his disciples: “If they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you.” Paul had assured them that “all that will live godly in Christ Jesus shall suffer persecution” (II. Tim. 3:12).The world, he had told them, would not be an easy place for Christians. Paul, himself, had endured much suffering and persecution during the course of his long ministry. For more than two decades he had persevered in preaching the gospel of the coming kingdom of God through many of the provinces of the Roman Empire. Now, at last, his sufferings are nearing an end.

Nero sends his servants to bring Paul word of his impending death. Shortly afterward, soldiers arrive and lead him out of the city to the place of execution. Paul prays, then give his neck to the sword. He is buried on the Ostian Way. The year is A.D. 68; it is early summer .Most of the remaining elders and members of the congregation at Rome are also martyred in the Neronian persecution. Peter----chief among the original twelve apostles----also meets his end in A.D. 68. He is condemned to death----as Jesus himself had foretold many years earlier (John 21:18-19)

Turmoil in Judea

Unfortunately, the headquarters church in Jerusalem----towards which Christians look for truth and for leadership----is in no position to render effective assistance to the persecuted Christians of Rome. It, too, is caught in the midst of upheaval, stemming from the Jewish wars with Rome. In A.D. 66, the oppressed Jews of Palestine erupt into general revolt—defying the military might of the Roman Empire! Heeding Jesus’ warning (Luke 21:20-21) the Christians of Judea flee to the hills .Later, in the spring of A.D. 69, the Roman general Titus finally sweeps from east of Jordan into Judea with his legions. The Christians escape impending calamity in the hills by journeying northeast to the out-of-the- way city of Pella, in the Gilead mountains east of the Jordan River. It is now A.D. 70. Titus conquers Jerusalem. He burns the Temple to the ground and tears down its foundations. The city is laid waste. Some 600,000 Jews are slaughtered and multiple thousands of others are sold into slavery. It is a time of unparalleled calamity!

Kingdom Imminent?

Amid all the upheaval in Rome, Judea and elsewhere in the Empire, what is the mood of the Christian community? What thoughts course through the minds of Christians at this time? Though many are suffering—uprooted from homes, imprisoned, tortured, bereaved of family and friends—the prevailing spirit among Christians is one of hope and anticipation.

Christians are sustained by the knowledge that Jesus and the prophets of old had foretold these tumultuous events—and their glorious outcome. As events swirl around them they watch with breathless expectations. They take hope in the great picture laid out by Jesus from the beginning of his earthly ministry—the return of Jesus Christ and the reestablishment of the kingdom of God! As Mark records: “Now after that John was put in prison. Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel [good news] of the kingdom of God, and saying, The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand: repent ye, and believe the gospel” (Mark 1:14-15)

Everywhere Jesus went, he focused on this major theme----the good news of the coming of the kingdom of God. The twelve disciples were sent out to preach the same message (Luke 9:1-2). The apostle Paul also preached the kingdom of God. (Acts 19:8; 20:25; 28:23, 31). Christians—in that first century—are in no doubt as to what that kingdom is. It is a literal kingdom—a real government, with a King, and laws and subjects----destined to rule over the earth. It is the government of God, supplanting the government of man!

Christians rehearse and discuss among themselves the many prophecies about this coming government. By now, they know the passage by heart. The prophet Daniel, for example, had written of a successions of world-ruling governments through the ages (Daniel 2)----four universal world-empires: Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome. Daniel declared that after the demise of these earthly kingdoms, “the God of heaven [shall] set up a kingdom, which shall never be destroyed....but it shall break in pieces and consume all these kingdoms, and it shall stand for ever” (Dan. 2:44).

This kingdom will rule over the nations. It will “break in pieces and consume” the Roman Empire----surely very soon, Christians feel! Soon the swords and spears spilling blood across the vast territories of the Empire would be beaten into plowshares and pruning hooks, as Isaiah had prophesied (Isa. 2:4). Jesus would return and “the government shall be upon his shoulders” (Isa. 9:6) For more than four millennia the righteous ancients had looked for the triumph of this kingdom. Now, with Jerusalem the focus of world events in A.D. 66-70, surely, it is about to arrive!

The Waiting

During the days of Jesus’ earthly ministry, some had thought he would establish the kingdom of God then and there. Because, they thought that the kingdom of God should immediately appear. Jesus had told his disciples the parable of the nobleman who went on a journey into a far country “to receive for himself a kingdom, and to return” (Luke 19:11-12) As Jesus later told Pilate, he was born to be king. But, his kingdom was not of this world (age) (John 18:36). He would return at a later time to establish his kingdom and sward his servants. His disciples no more understood that than did Pilate.

After his crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus’ disciples again asked him, “Lord, wilt thou at this time restore again the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6) Jesus told them that it was not for them to know the times or the seasons (verse 7). They found that hard to comprehend. But Jesus, nevertheless, commissioned them to “be witnesses unto me....unto the uttermost part of the earth” (verse *). For nearly four decades they had preached the gospel throughout the Roma world and beyond. Now, tumultuous events signal a change in world affairs. Signs of the end of the age----given by Jesus in the Olivet prophecy (Matthew 24)—seems to become increasingly evident of the world scene.

Rome, with civil war in A.D. 69, appears to be on a fast road to destruction. Wars, moral decay, economic crisis, political turmoil, social upheaval, religious confusion, natural disasters----all these signs are here. The very fabric of Roman society is disintegrating It is a rotten and a degraded world. Surely, Jesus will soon come to correct all that! That the Roman Empire is the fourth “beast” of Daniel’s prophecy (Daniel 7) is clear to Christians. With that fourth kingdom in the throes of revolution, God’s kingdom surely will come soon! Amid horrendous persecutions, martyrdoms and national upheavals, they wait for their change from material to spirit (I Cor. 15:50-53) and their reward of positions of authority and rulership in God’s .kingdom (Luke 19:17-19). I”I will come again.” said Jesus (John 14:3). Christians pray, “Thy kingdom come.”

They wait.

And wait.

But, it doesn’t happen

The Enigma

When Jesus does not return at the height and in the aftermath----of the cataclysmic events of A.D. 66-70, the shock is great. Many Christians are puzzled, disturbed, demoralized. It is a mystery—an enigma. What has “gone wrong?”The church is tested. Many face agonizing decisions. Many begin to doubt, and question.

The apostle Paul had once faced this issue. He had long expected Jesus’ return in his own lifetime. In A.D. 50, he had written to the Thessalonians of “we” which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord....” (I Thess. 4:15). Five years later, in a letter to the Corinthians, he had written that “we shall not all sleep [died]” before Jesus’ coming (I Cor. 15:51). But, in a letter to Timothy in the days just before his death, Paul clearly sees a different picture. He writes of the “last days” in a future context. (II Tim. 3:1-2.) He declares: “I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course....” (4:7). He speaks of receiving his reward at some future time (4:8), reward at some future time (4:8). Unlike Paul, however, many Christians become disheartened and discouraged. Their hopes are shattered. “Where is the promise of his coming?” many complain.

But some Christians understand. They realize that God intends that they face this question, to see how they will react. They wait and wait patiently, continuing in well-doing. They remember the words of Jesus, “Watch therefore: for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come....for in such an hour as ye think not the Son of man cometh” (Matt. 24:42, 44) It would be those who endure unto the end”—whenever that was----who would be saved (verse 13)

Some Christians----misunderstanding the final verses of the Gospel of John----believe that Jesus will yet return in the apostle John’s lifetime (John 21:20-23). As John grows progressively older—outliving his contemporaries----many see support for this view. They still wait for Jesus’ return in their generation. They wait.

But others are not so patient. They are restless, uneasy. They begin to look for other answers .Their eyes begin to turn from the vision of God’s kingdom and the true purpose of life. They lose the true sense of urgency they once had. They begin to stray from the straight path. They become confused—and vulnerable. Until the “disappointment,” false teachers had not made significant headway among Christians. Christians expected Jesus’ return at any time—they had to be faithful and ready at any moment! But now a large segment of the Christian community grows more receptive to “innovations” in doctrine. The ground is now ready to receive the evil seeds of heresy!

Another Gospel

Following the martyrdom of many of their faithful leaders, many Christians fall victim to error. Confused and disheartened, they become easy prey for wolves.

False teachers are nothing new to the Church. The crisis has been a long time in the making. As early as A.D. 50, Paul had declared to the Thessalonians that a conspiracy to supplant the truth was already under way. “For the mystery of iniquity doth ALREADY work,” he had written to them (II Thess. 2:7) Paul also warned the Galatians that some were perverting the gospel of Christ, trying to stamp .out the preaching of the grue gospel of the kingdom of God that Jesus preached (Gal. 1:6-7) He told the Corinthians that some were beginning to preach “another Jesus” and “another gospel” (II Cor. 11:4) He branded them “false apostles” and ministers of Satan (verses 13-15.)

Paul had often reminded the churches of the word of Jesus, that MANY would come in his name, proclaiming that Jesus was Christ, yet, deceiving MANY (Matt. 24:4-5, 11) The MANY----not the few----would be lead down the paths of error, deceived by a counterfeit faith masquerading as Christianity. The prophecy now comes to .pass. The situation grows increasingly acute. The introduction of false doctrines by clever teachers divides the beleaguered Christian community. It is split into contending factions, rent asunder by heresy and false teachings!

Unknown to many, this havoc in the Church represents a posthumous victory for a man who had sown the first seeds of the problem decades earlier. Notice what had occurred:

Simon the Sorcerer

A sorcerer named Simon, from Samaria (the one-time capital of the house of Israel), had appeared in Rome in A.D. 45, during the days of Claudius Caesar. This Simon was high priest of the Babylonian-Samaritan mystery religion (Rev. 17:5), brought to Samaria by the Assyrians after the captivity of the house of Israel (II Kings 17:24). Simon made a great impression in Rome with his demonic miracle-working —so much so that he was deified as a god by many of its superstitutious citizens.

Earlier, in A.D. 33, while still in Samaria, Simon (often known as Simon Magus—“The Magician”) had been impressed by the power of Christianity. He had been baptized, without adequate counseling, by Philip the deacon. Yet, Simon, in his heart, had not been willing to lay aside the prestige and influence he had as a magician over the Samaritans. So he asked for the office of an apostle and offered a sum of money to buy it. Jesus’ chief apostle, Simon Peter, sternly rebuked Simon the magician, told him to change his biter attitude and banned him from all fellowship in hope of future repentance. (Acts 8)

Traveling to Rome years later, Simon conspired to sow the seeds of division in the rapidly growing Christian churches of the West. His goal: to gain a personal following for himself. He seized upon the name of Christ as a clock for his teachings, which were a mixture of Babylonian paganism, Judaism and Christianity

He appropriated a Christian vocabulary to give a surface appearance to Christianity to his insidious dogmas.

By the time of his death, Simon had not fully succeeded in seducing the Christian community at large. But there were those who were attracted to certain of his compromising syncretistic ideas. Slipping unobtrusively into the Church of God, they subtly introduced elements of Simon’s teachings. Many fall victim to these false doctrines. Luke, writing the book of Acts in A.D. 62, exposes Simon in an attempt to stem his growing influence.

With Simon now exposed, those who had crept into Church fellowship, and who thought in part as he did, disassociate themselves from his name yet continue to promote his errors.. They are no longer known, or recognized as Simonians—but they hold the same doctrine! They assume the outward appearance of being Christians----preaching about the person of Christ----yet deny Christ’s message, the gospel of the coming kingdom of God.

A few years after Luke exposes Simon Magus, Jude writes of these Simonians as “certain men crept in unawares” (Jude, verse 4) and exhorts Christians to “earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered. (Verse 3) Also—as Paul had earlier prophesied (Acts 20:29-30)—some even within the Church of God departed from the original faith and because of personal vanity, a love of money or because of personal hurts ,begin to draw disciples away after themselves.

Heresies are rife! Sometimes, they are recognized, but often they are disguised and go undetected. Error creeps inn slowly and imperceptibly, gradually undermining the very truths of the Church that Jesus founded.

Another Shock

There remains one last obstacle to the complete triumph of heresy----the apostle John. is the last survivor of the original twelve apostles. He works tirelessly to stem the tide of error and apostasy.

Writing early in the last quarter of the first century, John declares that “many deceivers are entered into the world” (II John 7). He writes of the many who have already left the fellowship of the Church.(They went out from us, but they were not of us”—(I John 2:19) He revels that some apostate church leaders are even casting true Christians out of the church! (III John 9-10) During the persecutions of the Roman emperor Domitian, John is banished to the Aegean island of Patmos. Thedre he receives an astounding revelation.

In a series of visions, John is carried forward into the future, to the “day of the Lord”----a time when God will supernaturally intervene in world affairs, sending plagues upon the unrighteous and sinning nations of earth. And a time that will climax in the glorious Second Coming of Jesus Christ! The picture laid out in vision to John represents another major shock for the first-century Church. Here are astounding, almost unbelievable revelations! Images of multithreaded beasts, of great armies, of strange new weapons, of devastating plagues and natural disasters! What does it all mean?

New Understanding

After publication of the Revelation, those with understanding begin to grasp the message. It becomes clear to them that Jesus’ coming is not as imminent as once believed. Whole sections of the book of Daniel, previously obscure, now become clearer. These great events revealed to John by Jesus Christ will not occur overnight. Great periods of time appear to be implied----centuries, possibly even millennia!

Some few begin to see the teachings of Jesus in a new light. He had stated in his Olivet prophecy (Matt. 24:22) that “except those [last] days be shortened, there should NO FLESH be saved....” Many had wondered about this statement. They could not understand how there could even be enough swords, spears, and arrows----and men to use them----to even threaten the GLOBAL annihilation of all mankind.

Now, John’s vision provided an answer. There would one day come a time when never-before-heard-of superweapons-----described by John in strange symbolic language----would make total annihilation possible! ONE DAY.....but not now.

There will yet come a future crisis over Jerusalem, many also realize. There will come a time when Jerusalem will again compassed with armies (Luke 21:20) trigger a crisis even greater than that of A.D. 66-70.

Some also begin to realize that Jesus’ commission to his disciples to take the gospel “to the uttermost parts of the earth” might be meant literally! Jesus had prophesied that “this gospel of the kingdom shall be preached in all the world for a witness unto all nations; and THEN shall the end come” (Mast. 24-14). And that worldwide undertaking would require time----a great deal of time! Some few begin to see clearly. But many cannot handle this new truth. Some even begin to teach that the kingdom is already here----that it is the Church itself, or in the hearts of Christians.

John is released from imprisonment in A.D. 96. IN his remaining days he and faithful disciples strive to keep the Church true to the faith as he was personally instructed in it by Jesus himself. The First Century closes with the death of the aged apostle John in the city of Ephesus.

Jesus has not yet come. Some continue to wait. Others within and without the fellowship of the true Church of God.

PART TWO

THE FATEFUL UNION

THE CRISIS OVER JERUSALEM IN A.D. 70

HAS PASSED.

The civil turmoil within the Roman Empire temporarily ceases.

But the hopes of many Christians are shattered. Instead of being

delivered, Christians continue to suffer persecution as a result of Emperor

Nero’s example. Each day brings fresh news of the imprisonment or martyrdom of

relatives and friends.

Many Christians are confused. They thought the signs of the “end of the

age”—

including Roman armies surrounding Jerusalem (Luke 21:20)—had all been

there. Events had appeared to be moving swiftly toward the anxiously awaited

climax— the triumphal return of Jesus Christ as King of kings. But Jesus has not

returned. He should have come, many say to themselves. But he hasn’t. Divisions

set in among Christians. Then comes the Revelation of Jesus Christ to John, the

last surviving apostle. It explains that what occurred in A.D. 66 to 70 was only

a forerunner of a final crisis over Jerusalem at the end of this age of human

self-rule. The end is not now.

In disappointment or in impatience, many who call themselves Christians

begin to stray from the truth—or to renounce Christianity altogether. Those who

stray become susceptible to “innovations” in doctrine. Heresy is rife.

Congregations become divided by doctrinal differences even though they all call

themselves the Churches of God. Some begin to express doubts about the book of

Revelation, and press forward their own doctrinal views.

The apostasy foretold by the apostles moves ahead. Only the aged

apostle John stands in the way. The more than three decades since the death of

Peter and of Paul in AD. 68 have been spent under the sole apostolic leadership

of John. The churches directly supervised by him and faithful elders assisting

him have held firm to the government of God over the Church and to God’s

revealed truth. But now comes another shock. The apostle John dies in Ephesus.

At once, self- seeking contenders for authority grasp for power over the

churches. A full-scale rebellion breaks out against the authority of God’s

government as it has been administered by the apostles and then solely by the

apostle John.

Many lose sight of where and with whom God has been working. They turn

from the teachings of John and faithful disciples to follow others who claim to

have authority and preeminence and who call themselves God’s ministers. They

become the mainstream of professing Christianity.

But some remain faithful even though now separated from the mainstream

of Christianity. They hold fast to sound doctrine and resist the forces of the

invisible Satan who deceives the whole world. They continue to believe the good

news of the coming restoration of the government of God over the earth. They

continue to wait for Jesus to return with powçr to force world peace.

Persecution Continues

Regardless of their doctrinal differences whether apostate or

faithful—all who call themselves Christian continue to suffer persecution. The

polytheistic Romans are not by nature intolerant in religion. They permit many

different forms of belief and worship . They have even incorporated elements of

the religions of conquered peoples into their own.

But the various sects of Christianity pose a special problem. Adherents

to the various pagan religions readily accommodate themselves to the deification

of the emperor and the insistence that all loyal citizens sacrifice at his

altar. But this kind of “patriotism” goes far beyond what is possible for any

Christians. So they are punished not because they are Christians per se, but

because they are “disloyal.”

Nero, the first of the persecuting emperors, had set a cruel prece-ent. During the next 250 years, 10 major persecutions are unleashed upon Christianity. About A.D. 95, Emperor Domitian—the younger son of Vespasian and brother of Titus, des-troyer of Jerusalem—launches a short but severe persecution on Christians.

Thousands are slain in his reign of terror.

In AD. 98, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus—commonly known as Trajan—is elected

emperor by the Roman senate. In his eyes, Christianity is opposed to the state

religion and therefore sacrilegious and punishable. Among the many who die

during his reign is the influential theologian Ignatius, bishop of Antioch in

Syria, who is thrown to the lions in the Roman arena in AD. 110.

Trajan’s successors Hadrian (117-138) and Antoninus Pius (138-161)

continue the carnage. Among those to suffer martyrdom during the latter’s reign

is the illustr-ious Polycarp, elder at Smyrna and the leading Christian figure

in Asia Minor.

With the accession of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180), the Empire

suddenly finds itself disrupted by wars, rebellions, floods pestilence and

famine. As often happens in times of great disaster the ignorant populace seeks

to throw the blame for these calamities on an unpopular class in this case, the

various sects of Christians.

The strong outcry raised against what the world sees as Christianity

leaves Marcus Aurelius no choice. In troubled times as these, there can be only

one loyalty to the emperor . He orders the laws to be enforced. The resulting

persecution—the sever-est since Nero’s day—brings a horrible death to thousands

of Christians. Among them is the scholar Justin Martyr, who is put to death at

Rome.

The Roman emperors Septimius Severus (193-211) and Maximin (235-238)

continue the persecutions. Hunted as outlaws, thousands of Christians are burned

at the stake, crucified or beheaded. Emperor Decius (249-251) determines to

completely eradicate Christianity. Blood flows in frightful massacres throughout

the Empire . A subsequent persecution under Valerian (25 3-260) goes even

further in its severity.

But the persecution inaugurated by Diocletian (284-305) surpasses them all in violence. This 10th persecution is a systematic attempt to wipe the name of Christ from the earth! Diocletian’s violence towards the Christian sects is unparalleled in history. An edict requiring uniformity of worship is issued in A.D. 303. By refusing to pay homage to the image of the emperor, all Christians in the realm become outlaws. Their public and private possessions are taken from them, their assemblies are prohibited, their churches are torn down, their sacred writings are destroyed.

The victims of death and torture number into the tens—even hundreds—of

thousands Every means is devised to exterminate the obstinate religion. Coins

are struck commemorating the “annihilation of the Christians.” Only in the

extreme western portion of the Empire do Christians escape. Constantius Chlorus

Roman military ruler of Gaul, Spain, Britain and the Rhine frontier—prevents the

execution of the edict in the regions under his rule . He protects the

Christians, whose general virtues he esteems.

Civil War

Diocletian’s reign also brings a development of great historic impor-ance within the political realm. Diocletian realizes the Empire is too large to be administered by a single man. For purposes of better government of so vast an empire, Diocletian voluntarily divides the power and responsibility of his office, associating with himself his friend Maximian as co-emperor.

The two divide the Empire. Diocletian takes the East, with his capital

at Nicomedia in Asia Minor. Maximian takes the West and establishes his

headquarters at Milan in northern Italy. Each of these two Augusti or emperors

then selects an assistant with the title of Caesar. These deputy emperors are to

succeed them, and designate new Caesars in turn. The Caesars chosen by

Diocletian and Maximian are Galerius and Constantius Chlorus. They are to

command the armies of the frontiers.

After a severe illness, Diocletian abdicates his power on May 1, 305.

He compels his colleague Maximian to follow his example the same day. They are

succeeded by their respective deputy emperors, Galerius and Constantius. These

two former Caesars are now Augusti. Galerius rules the East; Constantius rules

the West.

When Constantius dies suddenly the next year while on expedition

against the Picts of Scotland, his troops immediately proclaim his son

Constantine as emperor. The smooth succession envisioned by Diocletian never

takes place. For the next eight years, there follows a succession of civil wars

among rival pretenders for imperial power. Constantine engages these competitors

in battle. The stage is now set forhistory-making events, within both the Empire

and Christianity.

Surprise in Rome

It is now 312. The persecution inaugurated by Diocletian nine years

earlier still rages. In Rome, Miltiades is bishop over the Christian groups

there. By this time, the bishop of Rome has come to be generally acknowledged

as the leader of Christ-ianity in the West. He is called “pope” (Latin, papa,

“father”), an ecclesiastical title long since given to many bishops.

(It will not be until the 9th century

that the title is reserved exclusively for the bishop of Rome.)

Of the 30 bishops of the Church at Rome before Miltiades, all but one

or two had died a martyr’s death. With a violent persecution underway, Miltiades

expects nothing better.

It is October 28. Miltiades emerges from his small house to discover

the great Constantine standing in the Street before him! With him are guards

with drawn swords. Constantine has just defeated his brother-in-law and chief

rival Maxentius (son of the old Western emperor Maximian) at the Milvian Bridge

near Rome. Winning this key battle has secured Constantine’s throne. He is now

sole emperor in the West.

But what does Constantine want of Miltiades? Does he intend to cap his

victory by personally executing the leader of Rome’s Christians? The emperor

steps forward. With Miltiades’ chief priest, Silvester, serving as interpreter,

Constantine begins to speak. What Miltiades hears signals

the beginning of a new era. The world will never

be the same again.

The Flaming Cross

Just before the battle of Milvian Bridge, Constantine had seen a

vision. In the sky appeared a flaming cross, and above it the words

In Hoc Signo Vinces (“In this sign,

conquer!”). Stirred by the vision, he ordered that the Christian symbol the

monogram xo (the superimposed Greek letters X and P.

Chi and Rho, the first two letters

of the word Christos)—be inscribed upon

the standards andshields of the army. The battle was then fought in the name of

the Christian God. Constantine was victorious. Maxentius was defeated and

drowned.

The crucial victory spells not only supreme power for Constantine, but

a new era for the Church. Constantine becomes

the first Roman emperor to profess Christianity, though he delays baptism

until the end of his life . A magnificent triumphal arch is erected in his honor

in Rome. It ascribes Constantine’s victory to the “inspiration of the Divinity.”

Soon afterward, Constantine issues the

Edict of Milan (313), granting Christians full freedom to practice their

religion. Thoughpagan worship is still tolerated until the end of the century,

Constantine exhorts all his subjects to follow his example and become

Christians. Constantine donates to the bishop of Rome the opulent Lateran

Palace. When Silvester is named bishop of Rome upon Miltiades’ death in January,

314, he is crowned—clad in imperial raiment—as an earthly prince. The emperor

fills many chief government offices with Christians and provides assist-ance in

building churches.

Things have indeed changed!

For centuries persecuted by the Empire, the Christian Church has now become

allied with it! Christianity assumes an intimate relationship with the secular

power. It quickly grows to a position of great influence over the affairs of the

Empire. Christians of decades past would not have believed it. They are free

from per-secution. The Emperor himself is a Christian! It is simply “too

good to be true.” Yet it is true!

Many Christians puzzle over this new order of things. For nearly three

centuries they had waited for the return of Jesus Christ as deliverer. They had

waited for the fall of Rome, and the triumph of the kingdom of God. But now the

persecutions have ended. The Church holds a position of power and respect

throughout the Empire. The picture appears bright for the faith! What does it

all mean?

Christians of various persuasions see many prophecies of persecution in

the Script-ures. But nowhere do Jesus or the apostles foretell a popular growth

and universal acceptance of the Church. No prophecy says that the Church of God

will become great and powerful in this world. Yet look what has happened! How is

it to be understood? After centuries of believing that the kingdom was “not of

this world” that the world and the Church would be at odds until Jesus’

return—professing Christians now search for an explanation to the new state of

affairs.

State Religion

Continuing events within the Empire further fuel this reevaluation. In

321, Const-antine issues an edict forbidding work on “the venerable day of the

sun” (Sunday), the day that had come to be substituted for the seventh-day

Sabbath (sunset Friday to sunset Saturday). Christians in general had hitherto

held Saturday as sacred, though in Rome and in Alexandria, Egypt, Christians had

ceased doing so. (In 365, the Council of Laodicea will formally prohibit the

keeping of the “Jewish Sabbath” by Christians.)

In 324, the Emperor formally establishes Christianity as the official

religion of the Empire . The previous year, Constantine had defeated the Eastern

Emperor and had become the sole Emperor of East and West. Thus Christianity is

now the established religion throughout the

civilized Western world! In an effort to further promote unity and

uniformity within Christianity, Constantine calls a conclave of bishops from all

parts of the Empire in 325. The council intended to settle doctrinal disputes

among Christians—is held at Nicea, in Bithynia.

The Council of Nicea confronts two major issues. It deals firstly with

a dispute over the relationship of Christ to God the Father. Thedispute is

called the Arian controversy. Anus, a priest of Alexandna, has been teaching

that Christ was created, not eternal and divine like the Father. The Council

condemns him and his doctrine and exiles Arian teachers. (The movement, however,

continues strong in many areas. When Gothic and Germanic invaders are converted

to Christianity, it is frequently to the Arian form.)

The other major issue at the Council is the proper date for the

celebration of Pass-over. Many Christians, especially those in Asia Minor—still

commemorate Jesus’ death on the 14th day of the Hebrew month Nisan the day the

“Jewish” passover lambs had been slain. In contrast, Rome and the Western

churches emphasize the resurrection, rather than the death of Jesus. They

celebrate an annual Passover feast—but always on a Sunday.

The Council rules that the ancient Christian Passover commemorating the

death of Jesus must no longer be kept—on pain of death. The Western custom is to

be observed throughout the Empire, on the first Sunday after the full moon

following the vernal equinox. It is later to be called “Easter” when the

Germanic tribes are con>verted en masse to Christianity. Most Christians accept

this decree. They constitute mainstream Christianity and the world accepts them

as such. But some refuse, and flee (Rev. 12:6) into the valleys and mountains of

Europe and Asia Minor to escape persecution and death. They continue, away from

the world’s view, as the true Church of God, lost in the pages of history.

The Fateful Union

As the majority of Christians view this new unity and uniformity within

the Church and the near universality of its influence, a revolution in thinking

takes place. There is now ONE Empire, ONE Emperor, ONE Church, ONE God. Many

Christians wonder: Is it possible they have not fully understood the concept of

the kingdom of God? Is it possible that the

Church itself or even the now-Christianized

Empire is the long-awaited kingdom of

God?

Or, might it be that God’s kingdom is meant to be established on earth

gradually, in successive stages? Could

Constantine’s edicts be the first step in this process?

This is a time of reevaluation, of deep soul-searching. Some few

declare the Church should wield no secular power—that such would be inconsistent

with the spirit of Christianity. Entangling itself with temporal affairs, they

assert, will only corrupt the Church from its true purpose. They declare that

the world is still the enemy only

it----outward tactics have changed.

But the majority feels differently. Here, they believe, is a great opportunity to spread their Christianity throughout the Empire and beyond. Hundreds of thou-sands---even millions----will be converted. The opportunity, they say, must be seized, not shunned! The fateful union of Church and State is thus ratified. That move shapes the course of civilization for centuries to come.

Church-State Confrontation

Constantine the Great dies on May 22, 337. Water is poured on his

forehead and he is declared “baptized” on his death bed. About a quarter century

after onstantine’s death, his nephew Julian (361-363) gains the throne. Julian

rejects the faith of his uncle and endeavors to revive the worship of the old

gods. His hatred of the Christ-ians gains for him the surname “Apostate.”

To spite the Christians, Julian patronizes the Jews, and even attempts

to rebuild their Temple in Jerusalem. He is thwarted, however, by “balls of

fire” issuing from the foundation, which makes it impossible for the workmen to

approach. Despite Julian’s efforts, the old stories of gods and goddesses have

lost their hold on the Roman mind. After Julian is killed while invading Persia,

Christianity returns to full prominence in the Empire.

In 394, under Emperor Theodosius (378-395), the ancient gods are

formally outlawed in the Empire. Conversion to Christianity becomes compulsory.

The power of the Church in Theodosius’ time is best illustrated in an incident

involving Ambrose, the archbishop of Milan. A man of savage temper, Theodosius

orders the massacre of about 7,000 people of Thessalonica, as a punishment for a

riot that had erupted there. The Thessalonians are butchered the innocent with

the guilty--- by a detachment of Gothic soldiers sentby Theodosius for that

purpose.

When the Emperor later attempts to enter the cathedral in Milan,

Ambrose meets him at the door and refuses him entrance until he publicly

confesses his guilt in the massacre . Though privately remorseful, the Emperor

is reluctant to diminish the prestige of his office by such a humiliation. But

after eight months, Theodosius the master of the civilized world—finally yields

and humbly implores pardon of Amb-rose in the presence of the congregation. On

Christmas Day, A.D. 390, he is restored to the communion of the Church. The

incident emphasizes the indepen>dence of the Western Church from imperial

domination.

Theodosius is the last ruler of a united Roman Empire. At his death the

Empire is divided between his two sons Honorius (in the West) and Arcadius (in

the East). Though in theory only a division for administrative purposes, the

separation proves to be permanent. The two sections grow steadily apart, and are

never again truly united. Each goes its own way towards a separate destiny.

Barbarian Inroads

Meanwhile, the restless Gothic and Germanic tribes to the north grow

stronger and more threatening to the peace of the Empire. For centuries the

Romans have fought off the barbarian hordes. Now these tribes begin to move into

the Empire in force. Not all, however, have come as enemies . For decades many

tribes have been coming across the Roman frontiers peaceably, as settlers. Many

Germans are now serving in the Roman army, and some in the imperial palace

itself.

When Emperor Theodosius dies (395), one of these Germans is even named

as guardian of his young son Honorius. He is Stilicho, a “barbarian” of the

Vandal nation. A brilliant general, Stilicho repeatedly beats back attempted

invasions of Italy by various barbarian tribes. Most troublesome of all is

Alaric the Visigoth. Stilicho repels numerous assaults by Alaric into the

peninsula. But Honorius is jealous of the general who has so often saved Rome.

In August, 408, he has Stilicho assassinated. The news of his death rouses

Alaric to yet another invasion.

For a costly ransom, Alaric spares Rome in 409. But the next year he

comes again. On August 10, AD. 410, Alarie takes the “Eternal City,” and for six

days Rome is given up to murder and pillage. For the first time in nearly 800

years, Rome is captured by a foreign enemy!

It is a profound shock. Many cannot believe it. When Jerome----the translator of the Bible into Latin ----hears the news in Bethlehem, he writes:

“My voice is choked, and my sobs interrupt the words I write.

The city which took the whole world is herself taken. Who could

have believed that Rome, which was built upon the spoils of the

earth, would fall?”

Many bemoan the event as the fall of the Western Roman Empire. But

there is still an emperor on the imperial throne. In a ceremonial way, at least,

the Empire continues.

Alaric withdraws from the city and dies soon afterward. Rome grants the

Visigoths the richest parts of Gaul as a permanent residence. By the middle of,

the 5th century, barbarian tribes are occupying most parts of the

Western Roman Empire.

Papal Peacemaking

Of all the barbarian tribes, perhaps the non-Germanic Huns are the most

feared of all. A nomadic people moving out of Central Asia, they are led by the

famous Attila, known to the world of his time as the “Scourge of God.” In 451,

Attila invades Gaul, his objective being the kingdom of the Germanic Visigoths.

The Roman General Aetius—massing the combined forces of the Western Empire and

the Visigoths holds his own against Attila near Chalons. It is called “the

battle of nations,” one of the most memorable battles in the history of the

world. It is Attila’s first and only setback.

Though checked, Attila’s power is not destroyed. The next year (452)

Attila appears in northern Italy with a great army. Rome’s defenses collapse.

The road to Rome lies open before Attila. Its citizens expect the worst. But

Rome is spared. Attila withdraws when success lies just within his grasp. The

threatened march on Rome does not take place! What has happened?

The bishop of Rome at this time is a man named Leo. He has traveled

northward to the river Po to meet the mighty Attila. There is no record of the

conversation be-tween the two. But one fact is clear. A fearless diplomat, Leo

has confronted the “Scourge of God” and won. He has somehow persuaded Attila to

abandon his quest for the Eternal City. Attila dies shortly afterward. The Huns

trouble Europe no more.

The prestige of the papacy is greatly enhanced by Leo’s intervention on

behalf of Rome. As the civil government grows increasingly incapable of keeping

order, the Church begins to take its place, assuming many secular

responsibilities. History will record that it was Leo the Great who laid the

foundations of the temp-oral power of the popes. Leo has become the leading

figure in Italy!

In the religious sphere, Leo strongly asserts the primacy of Rome’s

bishop over all other bishops. Earlier in the century, the illustrious

Augustine, bishop of Hippo in North Africa, had uttered the now-famous words,

“Rome has spoken; the cause is ended.” At the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the

assembled bishops responded to Leo’s pronouncements with the words: “Peter has

spoken by Leo; let him be anath-ema who believes otherwise.” The doctrine that

papal power had been granted by Christ to Peter, and that that power was passed

on by Peter to his successors in Rome, begins to take firm root.

In June, 455, Geiseric (Genseric)—the Vandal king of North

Africa—occupies Rome. Again Leo saves the day. Leo induces Geiseric to have

mercy on the city. Geiseric consents to spare the lives of Rome’s citizens,

demanding only their wealth. Leo’s successful intervention further increases the

prestige and authority of the papacy, within the Empire as well as the Church.

The Deadly Wound

But the city of Rome is fast dying, and even the papacy’s efforts

cannot save her. The Empire lives only in a ceremonial sense. The Western

emperors are mere puppets of the various Germanic generals. Now even the

ceremony is about to be stripped away.

It is 476. A boy-monarch sits on the throne in Rome.

His name is Romulus Augustus, but he is satirically dubbed

“Augustulus,” meaning “little Augustus.” By curious coincidence, he bears the

names of the founder of Rome (Romulus) and of the Empire (Augustus) -----both of

which are about to fall.

The German warrior Odoacer (or Odovacar)-- a Heruli chieftain ruling

over a coal-ition of Germanic tribes—sees no reason for carrying on the sham of

the puppet emperors any longer. On September 4, 476, he deposes Romulus

Augustulus. The long and gradual process of the fall of Rome is now complete.

The Western Empire has received a mortal wound. Rome has fallen. The

office of Emperor is vacant. There is no successor. The 2 former mistress of the

world is thebooty of barbarians. Zeno, the Eastern Emperor at Constantinople

(founded by Constantine in 327 as the new capital for the Eastern half of the

Empire), appoints Odoacer patricius (“patrician”) of Italy. But in reality,

Constantinople has little power in the West. Odoacer is an independent king in

Italy.

Silent Forces

With the fall of the Western Empire, ancient history draws to a close.

A transitional period follows. Every portion of the Western Empire is occupied

and governedby kings of Germanic race. Many of these barbarian kings are, like

Odoacer, converts to Arian Christianity, opposed to the “Catholic” Christianity

of Rome.

But their kingdoms are not destined to endure. Forces are already

silently at work, forces seeking to mold out of the ruins of the old Western

Empire a revived and revitalized Roman Empire—a

non-Arian Empire!

These forces will ultimately succeed in healing the deadly wound of A.D. 476---- with epoch-making. consequences.

Part Three

The Imperial Restoration

ROME HAS FALLEN!

The greatest power the world has ever known is trampled in the dust. The Empire that had conquered the world is herself conquered!

Italy is overrun by Germanic tribes. Odoacer, a

chieftain of the Germanic Heruli, has deposed the boy-monarch Romulus Augustulus.

The great city is without an emperor!

The long and gradual collapse is now complete.

The ancient world is at an end. The Middle Ages have begun.

The stage is now set for momentous events--- events that will

determine the course of history for centuries to come.

Master of Italy

In the East, the old Roman Empire still lives, protected by the almost impregnable walls of Constantinople. There, Zeno sits on the throne of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire. In theory, the German Odoacer accepts the overlordship of Emperor Zeno. Zeno considers Italy one of the administrative divisions of his empire.

In reality, Constantinople has little power west of the Adriatic. Odoacer holds the administration of Italy firmly in his own hands. He is master of the peninsula.

Odoacer perpetuates the Roman form of government, which he admires. He initially encounters little serious opposition from the people of Italy. But Odoacer is an Arian Christian; that is, a Christian who follows the teachings of the scholar Anus. The Italians, by contrast, are Catholics.

The same is true in North Africa. There, the Germanic Vandals have held sway since AD. 429. The Vandals, too, continue and maintain the Roman system of administration within their kingdom. The Vandals are also Arian Christians. They persecute the Catholics within their realm, often fiercely. The Roman Catholic Church bristles under the feet of the Arian barbarians dominating the West. Since the days of Constantine, the Church had had the wholehearted support of the civil power. Now things have changed radically—for the worst. Something will have to be done about these hated Arian heretics.

Italy’s New “King”

In AD. 476—the same year Odoacer deposes the last Roman emperor—a young noble named Theodoric becomes leader of the Ostrogoths (East Goths). Theodoric quickly becomes the most powerful of the barbarian kings in southeastern Europe.

Zeno, the Eastern emperor, fears the ambitious Theodoric. To prevent the trouble-some Ostrogoths from invading his Eastern Empire, Zeno recognizes Theodoric as king of Italy” in 488. Zeno hopes to appease Theodoric, thereby ridding himself of the Ostrogothic menace.

Theodoric immediately leads 100,000 Ostrogoths into Italy to claim his kingdom from Odoacer. By the autumn of 490, Theodoric has captured nearly the entire peninsula. But throughout Italy, military garrisons still hold towns for Odoacer. These bastions must be eliminated!

Secret Plot

Though Theodoric is himself attached to the Arian creed, he is supported by the Catholic clergy in Italy. The clergymen feel they will fare better under Theodoric than under Odoacer. Secret orders are sent to the overwhelmingly Catholic citizenry throughout Italy. The Heruli and other soldiers still loyal to Odoacer are to be dealt with once and for all!

The secret of the plot is well kept. It is executed precisely on time. The Heruli are caught completely off guard. Throughout Italy, Catholic civilians set upon the unsuspecting Heruli at a predetermined hour. At ones stroke, the Italian citizenry accomplishes what the Ostrogoths could not. This “sacrificial massacre” (as one contemporary describes it) puts an end to Heruli as a military power once and for all.

Ambush!

Beaten in the field, Odoacer has taken refuge behind the strong fortifications of Raven na, north of Rome. There he is besieged nearly three years. Early in 493, Odoacer finally surrenders. Theodoric graciously offers to rule Italy jointly with him. A few days later on March 5, 493 Theodoric invites Odoacer to a banquet. Odoacer accepts—with disastrous consequences. As Odoacer enters the banquet hail, two of Theodoric’s men suddenly grasp his arms. Others hidden in ambush rush forward with drawn swords. Apparently they had not been told the identity of their intended victim, for when they see Odoacer standing helpless before them they are panic-stricken!

The soldiers hesitate. Theodoric himself rushes forward to do the job for them. With one powerful blow of his broadsword, Theodoric splits Odoacer in two from his collarbone to his hip! With this piece of treachery, Theodoric becomes the sole and undisputed master of Rome. Heestablishes a strong Gothic king-dom in Italy. Theodoric, too, has great respect for Roman civilization, and continues the tradit-ional Roman system of government.

But Theodoric and his heirs are Arians. And for this reason, they, too, will have to be uprooted. Theodoric dies in Ravenna on August 30, 526. He has no male issue, so his kingdom is divided among his grandsons. Civil war soon breaks out in Italy—with dire consequences for the Ostrogothic nation.

New Rome

Meanwhile, Constantinople is growing in importance. As the western part of the Roman Empire had gradually succumbed to the barbarians, the star of the eastern capital had steadily risen. Emperor Constantine had begun building the magnificent new capi tal of the Roman Empire in AD. 327. He had called it Nova Roma— ”New Rome.” It was founded on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium. Before Byzantium became New Rome, it had occupied the favored location on the Bosporus for more than 1,000 years.

With the fall of Rome, Constantinople and its emperors carry on the traditions of Roman civilization. Emperor Zeno who had made Theodoric king of Italy—is followed as emperor by Anastasius (491-518). Anastasius is succeeded by Justin (518-527). In August 527—exactly a year after Theodoric died heirless in Ravenna, a new emperor comes to the throne of the Eastern Empire. The childless Justin is succeeded by his nephew and protégé Justinian. He will rule for nearly four decades.

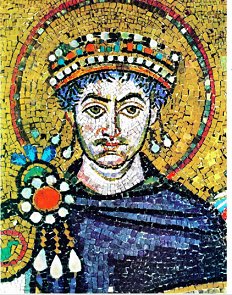

Justinian is 45 years old. He possesses great intelligence and boundless energy. He is popularly called “the man who never sleeps.” Beside Justinian at the helm of state is his beautiful wife and empress, Theodora. Justinian had married her four years earlier, in 523. Theodora is lowborn . She is a former actress and dancer. Her father had been a bear trainer at the Hippodrome circus. Vicious rumor declares her to have once been a prostitute. The truth of this charge will be debated for centuries. Despite her past. Theodora be comes a queen in every sense of the word. Her personal morals as empress will never be called into question. For 21 years, until her death from cancer in 548. she will live with Justinian as his faithful spouse and adviser. Theodora is brilliant, brave and wise. Had she been otherwise, Justinian would not have held his throne. And his historic mission—a mission of the highest significance to the course of history—would never have been realized.

“Conquer!”

Justinian’s career is almost ended before it begins. Constantinople is a sports-minded city. Its people are divided in their allegiance to different charioteers. They are called the Greens and the Blues, according to the color of dress of their favorite jockeys. In January 532, a disturbance breaks out between the two factions. The ringleader of each party is punished. In response, the two rival factions unite in armed revolt against the government. Open violence erupts as the government cracks down on both factions. The city is filled with fire, bloodshed and murder. Thousands are slain in the rioting. The crowd cries out “Nika!” (Greek for “Conquer!”). History will thus record the event as the “Nika Riots.”

Justinian’s life stands in jeopardy. He decides to abdicate, and prepares to abandon his capital by ship. But at the last moment he is dissuaded by Empress Theodora. In a bold speech, Theodora turns the tide of her husband’s fear. “I will remain, and like the great men of old, regard my throne as a glorious tomb,” she declares. Her r firm stand arouses new determination in Justinian. He de cides to stand his ground.

Justinian dispatches Belisarius, his trusted and brilliant general, to i the Hippo-drome with 3,000 veter ans. The riots are decisively suppressed. In one day, Belisarius slaughters 30,000! Justinian’s throne is saved. Had the Emperor been toppled, history might have taken a much different course.

Burning Ambition

Justinian is now in a position to pursue his one burning ambition: the recovery of the Western provinces that his predecessors had lost to the barbarians. His dream is to restore the Roman Empire to its full ancient grandeur—under his s own scepter! Justinian sees himself a as rightful ruler of the whole Roe man world. But Justinian realizes that there cannot be unity of empire without unity of religion.

Throughout the Empire—West and East Christianity is established. But the form of Christianity is not the same everywhere. Quarrels over basic articles of faith tear it at the unity of Christendom. Justinian believes that a theological rapprochement will prepare the way for the eventual political reunion of Byzantium and Italy. He views political and ecclesiastical policy as inextricably linked. They are the two major aspects of his envisioned Christian Empire. One of the most divisive religious controversies centers around the old argument about the union of the human and the divine in Jesus Christ. Some believe that Christ had only one nature—a divine one or rather than a combined human and as divine nature, as Catholics believe. They are called “Monophysites”—believers in one nature. The West—led by the Pope in Rome—rejects the Monophysite doctrine, charging that it over stresses the divine in Christ at the expense of the human. In AD. 45 1, the Council of Chalcedon (held in what is now modern Turkey) condemns Monophysitism as heresy, just as the Council of Nicaea had condemned Arianism in 325.

But Monophysitism persists. The Eastern Church is torn between Catholic ortho-doxy and the Monophysite doctrine. Zeno and his successor Anastasius sympathize with the Monophysites, triggering a schism between Constantinople and Rome. The Monophysites are powerful in the Eastern provinces of Egypt and Syria. The Eastern emperors do not want to endanger their control of these provinces by condemning the doctrine.

Ecclesiastical Dilemma

Upon the accession of Justin in 518, good relations are renewed with the Papacy. Communion is reestablished with Rome. The Eastern prelates sign a letter of reconciliation proclaiming the decision of Chalcedon as binding on all Christians and stressing the primacy of the Roman See as the final arbiter of what constitutes the faith.

The authority of Chalcedon is thus renewed. The Eastern and Western churches are, for a time, reconciled, albeit tenuously. But this does not end the problem. Monophysitism still thrives in many areas. Personally, Justinian is a most zealous supporter of the Council of Chalcedon and the cause of orthodoxy. But he would like to somehow unite the die-hard Monophysites with the Church. He seeks to placate the Monophysites without offending Rome a difficult task. He will have but slight success.

Justinian’s efforts are hampered by the sympathies of Empress Theodora. She leans toward the Monophysite position. In 536, Theodora intrigues with Vigilius, a Roman deacon. Succumbing to an impulse of ambition, he agrees to modify Western intransigence toward the Monophysites in exchange for her helping him become Pope. It is said he gives Theodora a secret guarantee that he will use his papal influence to abolish the Council of Chalcedon. The next year, Vigilius is installed as Pope. But Theodora’s hopes of manipulating the Roman See are disappointed. Under many opposing pressures, Vigilius vacillates and fails to offer clear concessions to the Monophysites. For years the problem continues to plague the religious world. The situation grows so acute that Justinian is finally prompted to convoke a general church council. In May 553, the Second Council of Constant-inople (the Fifth Ecumenical Council) opens . It has been called in yet another attempt to reconcile the Monophysites. The issues are complex. The Council finally settles on an interpretation that is technically orthodox but leans a bit toward the Monophysite position.

Few are satisfied with this compromise formula. To the Monophysites, the new interpretation is just as unacceptable as the old. Pope Vigilius initially refuses to accept the decrees of the Council. But under pressure he later signs a formal statement (February 554) giving pontifical approbation to the Council’s verdict. In return, Justinian grants Vigilius an imperial document known as the Pragmatic Sanction and permits him to return from Constantinople to Rome. Vigilius dies on the way back. A new Pope, Pelagius, is eleeted—with Justinian’s insistence.

Justinian’s Pragmatic Sanction confirms and increases the Papacy’s temporal power, and gives guidelines for regulating civil and ecclesiastical affairs in Rome and Italy. It is issued on August 13, 554. The year 554 will become a decisive date in history for yet another reason—the result of events in the military arena.

For the moment, the Papacy is under the Eastern Emperor’s thumb. But it is not destined to remain so. Ultimately, Justinian’s efforts in the religious sphere prove fruitless. At his death, the Empire will still be badly divided in its religious belief. The unhealed wounds of reigious strife between the churches of East and West will continue to fester—coming to a head, as we shall see, in the Great Schism of 1054.

Barbarians Smashed

While the aforementioned ecclesiastical maneuverings are underway, events are moving swiftly ahead in the political sphere. The persecuted Catholics in North Africa appeal to Justinian to send troops against their Arian andal oppressors. This sparks the short-lived Vandalic Wars. Justinian sends Belisarius—the greatest general of his age to do the job. In 533-34, imperial armies move against the Vandals. Belisarius makes short work of the barbarians. He receives the submission of the Vandal king Gelimer, and North Africa is reincorporated into the Empire.

Phase Two of Justinian’s Grand Design follows immediately: the military re-conquest of Italy, the heart and mother province of the Western Empire. The Ostrogoths have played into Justinian’s hands. In his latter years, Theodoric had begun to persecute the Catholic Italians. Following his death, Ostrogothic cruelty toward non-Arians intensifies. Italians look for a deliverer to uproot Arianism.

Justinian now has an excuse for invading Italy. He sees himself as God’s agent in destroying the barbarian heretics and winning back the lost provinces of the West. If he succeeds in toppling the barbarian usurper from the Western throne, his dream of restoring the Roman Empire will become reality!

Italy Regained

In 535, Belisarius fresh from victory in North Africa—arrives in Italy to take on the Ostrogoths. Italy is plunged into war. The fighting will continue for nearly two decades. In 540, Belisarius captures Ravenna and announces the end of the war. But the Goths soon regroup under a new king, Totila, and again take the offensive. City after city falls to Totila, including Rome in 546. (Totila holds the last chariot races in Rome’s Circus Maximus in 549.) In 549, Belisarius is recalled to Constantinople. In 552, Justinian sends a strong force against Totila under the command of General Narses. Totila is defeated and mortally wounded in the summer of 552. His body is placed at the feet of Justinian in Constantinople.

By 554, the Gothic hold is completely broken. The reconquest of the peninsula is complete. Italy is regained! Italy is now firmly in Justinian ‘s hands. His Pragmatic Sanction of 554 (mentioned previously) officially restores the Italian lands taken by the Ostrogoths. Italy is again an integral part of the Empire. Three barbarian Arian kingdoms have been uprooted and swept away! The deadly wound of AD. 476 is healed! The ancient Roman Empire is revived ----restored under the scepter of Justinian. Both “legs” of the Empire—East and West—are now under his personal control. History will memorialize his great achievement as the “Imperial Restorat- ion.” It is a milestone in the story of mankind.

Heir of the Caesars

Many territories have been regained. During his reign, Justinian t has doubled the Empire’s extent! The great Emperor dies on November 14, 565. He has lived 83 years and reigned 38. At his death, his restoration is ready to crumble. The resources of the Empire are not sufficient to maintain those territories that have been recovered. The treasury is empty. The army is scattered and ill paid. Within a century after his death, the Empire will have lost more territory than .Justinian had gained! Just three years after his death, the Longobardi, or Lombards—a Germanic tribe—invade and conquer half of Italy . Again the Eastem Empire is deprived of the greater portion of the Italian peninsula. The continuing threat of the Empire’s traditional enemy to the east Persia—further saps Byzantium’s strength. And soon, the forces unleashed by Mohammed in Arabia will introduce yet another peril. In the meantime, the Roman court of the East will lose much of its Western character.

For

these and other reasons, the focus of events will now shift to the West. As the

Eastern Empire founders, Papal Rome will turn its eyes toward Western Europe,

where the powerful Frankish kingdom is on the rise. Subsequent revivals of the

ancient Roman Empire will surface in France, Germany and Austria. The center

will shift away from the Mediterranean to the heart of Europe. But Justinian’s

efforts are not to be slighted. His reign has signaled a rebirth of imperial

greatness. He has been a true Roman emperor, an heir of the Roman Caesars! Much

of what will be envisioned and accomplished by later conquerors who build upon

the ruins of the Roman Empire will be owed to the memory of the Grand Design of

Justinian. The historical consequences will be major.

For

these and other reasons, the focus of events will now shift to the West. As the

Eastern Empire founders, Papal Rome will turn its eyes toward Western Europe,

where the powerful Frankish kingdom is on the rise. Subsequent revivals of the

ancient Roman Empire will surface in France, Germany and Austria. The center

will shift away from the Mediterranean to the heart of Europe. But Justinian’s

efforts are not to be slighted. His reign has signaled a rebirth of imperial

greatness. He has been a true Roman emperor, an heir of the Roman Caesars! Much

of what will be envisioned and accomplished by later conquerors who build upon

the ruins of the Roman Empire will be owed to the memory of the Grand Design of

Justinian. The historical consequences will be major.

Mosaic of the imperial retinue in the choir,

San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy. Laid prior to A.D.

547, detail shows Emperor Justinian.

Part Four

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

J USTIN IAN’S RESTORATION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE WEST IN A.D. 554 is a landmark in history. For a brief moment, both “legs” of the old Roman Empire East and West are under his personal control. But Justinian’s history-making restoration barely survives him.

With the great Emperor’s death, the Eastern Empire, with its capital at Byzantium, falls into a period of weakness and decline. At home, civil and religious strife tear at the fabric of society. To the east, the Persians renew their wars. To the west, the Germanic Lombards invade and conquer much of Italy.

Justinian’s “Imperial Restoration’’ crumbles into the dustbin of history. Though dying of lethargy, the Eastern Roman Empire, long since known as Byzantium, continues to be recognized as the eastern successor of the old Roman Empire . This weakened eastern leg will stand precariously for another millennium.

Meanwhile, papal Rome turns its eyes toward Western Europe. There, a powerful kingdom to the northwest is on the rise—the kingdom of the Franks. The Franks earlier had settled along the Rhine after migrating up the Danube River. It will be under Frankish tutelage that the western leg of the Roman Empire will rediscover its vitality and strength.

The Long-haired Kings

The Frankish tribes are ruled by a royal family of kings known as the Merovingians. The Merovingians claim direct descent from the royal house of ancient Troy. The Merovingian rulers possess an unusual mark of authority. All the kings of this dynasty wear long hair. They believe that their uncut locks are the secret of their kingly power, reminiscent of the nazarite vow of Samson in the Old Testament (Judges 13:5; 16:17; see also Numbers 6:5).

The Merovingian dynasty had been founded by Clodion in AD. 427. But its most famous ruler is Clovis (481-511). Later historians will consider Clovis to have been the founder of the Frankish kingdom.

On December 25, 496, Clovis is baptized a Catholic, along with 3,000 of his own warriors. He thereby becomes the first Catholic king of the Franks and the only orthodox Christian ruler in the West. Upon Clovis’ death in 511, his kingdom is divided among his sons, who further enlarge its borders. The Frankish kingdom rapidly becomes the West’s most powerful realm. With the passage of time, however, the old line of Frankish kings grows weak. The decadent Merovingian kings succumb to luxurious living. They will be designated by French historians as les rois fainéants—’ ‘the enfeebled kings.” During this period, the real power of the Frankish kingdom lies in the hands of the court chancellors, who are known as major domus regiae, or “mayors of the palace.”

“God’s Anointed”

It is now 751. Pepin (or Pippin), surnamed Le Bref (“the Short”), holds the office of mayor of the palace under the Merovingian king. Pepin, of course, is also a German Frank by blood and speech. Pepin the Short is ambitious. He is not content to be merely the king’s chief minister or viceroy. He covets the office of king itself.

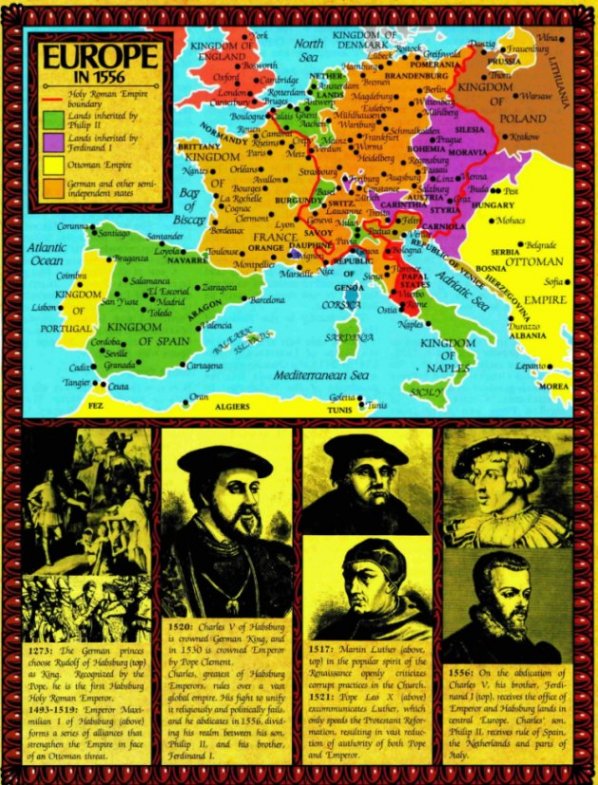

Pepin asks Pope Zacharias for an opinion on the legitimacy of his bid. The Pope replies that “it is better that the man who has the real power should have the title of king instead of the man who has the mere title but no power.” In November 751, Archbishop Boniface, the papal legate, anoints Pepin king of the Franks at a gathering of Frankish nobles in the Merovingian capital at Soissons. Pepin is now “God’s anointed” and the Merovingian king Childeric III is deposed and imprisoned. His sacred flowing hair is ritually shorn by the command of Pope Stephen II (752-757). The power of the Merovingians is broken!

Childeric is sent to a monastery for the rest of his days. The Merovingian bloodline, however, will survive, through intermarriage, in the line of the dukes of Hapsburg- Lorraine. The Merovingians have reigned by right of conquest. But Pepin has now assumed the sovereignty in the name of God. He believes it is God’s will that his family rule the Franks. Pepin accordingly styles himself rex gratia Dei (“king by the grace of God”), a title retained by his successors. Pepin’s new dynasty will be known as the Carolingians. The name derives from Pepin’s father, Charles (Carolus) Martel, who had been mayor of the palace before him. It had been Charles Martel (“the Hammer”) who saved Europe from the invading Saracens at Tours, in France, in October 732. By that momentous victory, the Franks had become widely recognized as the real defenders of Christendom. The Papacy had long since realized that Byzantium could defend no one.

Lombard Threat

The Church now looks to the Carolingians for protection against the Germanic Lombards, who are occupying much of Italy—and want the rest! The situation becomes desperate. As the Lombards threaten Rome, Pope Stephen II sets out across the stormy Alps in November 753. His goal is Pepin’s winter camp. The Pope asks Pepin to come to his aid. The Church must be protected from the encroachment of the Lombards!

At the same time, Pope Stephen 7 personally anoints and crowns Pepin, and blesses Pepin’s sons and heirs. The Franks answer the call Pepin invades Italy and defeats the Lombards. He then confers the conquered Lombard territory upon the Pope (754). This gift of rescued lands is called the “Donation of Pepin.” It cements the alliance between the Carolingians and the Church. (The Donation of Pepin is not to be confused with the fictitious “Donation of Constantine, a forgery also dating from about this time. This document—whose falsity would not be proved for another 700 years—ostensibly came from the pen of the Emperor Constantine himself early in the fourth century, when he moved to the new capital of Constantinople. The document purports to be an offer from Constantine to Pope Sylvester I and his successors of temporal rulership over Rome, over Italy and over most territories of the Western world! Believed to be genuine, the parchment carries vast implications and bolsters significantly the prestige and authority of the Papacy.)

New King

Pepin dies in 768. His sons Charles (Karl) and Carloman jointly succeed to the Frankish throne. In 771, Carloman dies suddenly, and Charles becomes sole king of the Franks. Though only 29 years old Charles is an imposing figure He most literally exudes power and authority! Charles is 7 feet tall— well over a foot above average height and robust. He is stately and dignified in bearing, but is known for his warmheartedness and charity. He speaks a type of Old High German. But most important, he is a zealous and dedicated Catholic Christian!

Now in undisputed possession of the Frankish throne. Charles directs his efforts against the enemies of his kingdom. His great goal is to reestablish the political unity that had existed in Europe before the invasions of the fifth century.

He first launches a campaign against the fierce Saxons, who are threatening his frontiers . The Saxons are the last great pagan German nation. During the next three decades, Charles will wage 18 campaigns in his costly and bitter struggle against the stubborn Saxons. In 804 they will finally be Christianized at the point of the sword and incorporated into his empire. Charles also undertakes campaigns against the Bavarians, Avars, Slays, Bretons, Arabs and 35 numerous other peoples. During his long career, he will conduct 53 expeditions and war against 12 different nations! And in the process he will unite by conquest nearly all the lands of Western Europe into one political unit.

Urgent Plea

Pepin had delivered a crushing defeat to the Lombards, but he had not totally subdued them. The Church is now threatened once more. Rome needs a champion! In 772, Charles receives an urgent plea for aid from Pope Adrian I, whose territories have been invaded by Desiderius, king of the Lombards. So, Charles crosses the Alps from Geneva with two armies. In 774 he decisively overthrows the kingdom of the Lombards, deposes Desiderius and proclaims himself sovereign of the Lombards.

Charles is now master of Italy! Charles takes the title Rex Francorum et Long-obardorum atque Patricius Romanorum (“King of the Franks and Lombards and Patrician of the Romans”). The famous iron crown” of the Loinbards which will become one of the great historic symbols of Europe is placed upon Charles’ head. It will be used in subsequent centuries by Napoleon and other sovereigns of Europe.

Charles confirms and expands the Donation made to the Papacy by his father. This territory will later be known as the States of the Church. Italy is again united for the first time in centuries. Charles is heralded as defender of the Church and the guardian of the Christian faith. The Frankish monarchy and the Papacy stand in partnership against the enemies of civilization! Charles is now the most conspicuous ruler in Europe. History will know him as Charlemagne—“Charles the Great.”

Papal Misconduct?

It is 795. There is a new Pope—Leo III.---in Rome. He immediately recognizes Charles as patricius of the Romans. By now, Western Christendom fully recognizes the bishop of Rome as its head. But there are elements within the city of Rome itself that wish to see Leo deposed and another candidate crowned as Pope in his stead.

In the spring of 799, Pope Leo is accused of misconduct. Adultery, perjury and simony are among the charges. He is driven out of Rome by an insurrection, and is granted refuge at the court of Charlemagne, protector of the Holy See. Charlema -gne reserves judgment, and has Leo escorted back to Rome. In November 800, Charlemagne himself comes to Rome to investigate the charges. A bishop’s commission of inquiry into Leo’s conduct is set up. Charlemagne presides over the tribunal.

Pope Leo swears on the Gospels that he is innocent of the crimes alleged against him. The judgment of the tribunal is in his favor. Leo is formally cleared and reinstated on December 23. On the same day, emissaries from Harun al-Rashid, caliph of Baghdad, arrive in Rome with the keys to the Holy Sepulchre in Jeru-salem. (Jerusalem lies within the extensive domains of the caliph.) The keys are officially presented to Charlemagne. This act symbolizes the Moslem caliph’s recognition of Charlemagne as protector of Christians and Christian properties.

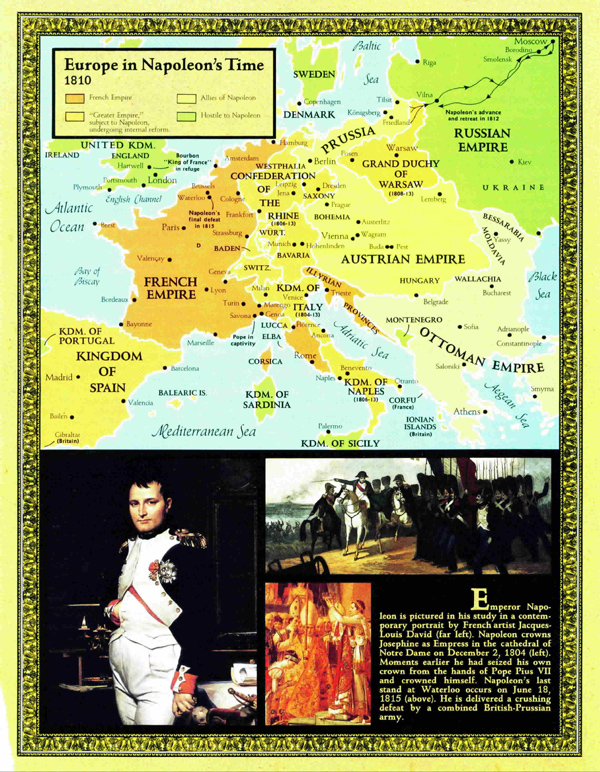

Central Event

Charlemagne remains in Rome for the Christmas holidays. On Christmas Day, A.D. 800, the king of the Franks attends a service in St. Peter’s Basilica on Vatican Hill. The stage is now set for one of the great scenes of all history. Charlemagne kneels before the altar in worship. There is a dramatic hush in the church. As the great king rises, Pope Leo without warning, suddenly turns around and places a golden crown on the monarch’s head! Immediately the assembled people cry in unison: “Long life and victory to Charles Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-giving Emperor of the Romans!”

The Pope has crowned Charlemagne as imperator Romanorum—”Emperor of the Romans”! Something profound has occurred. The West once more has an emperor! Historians will look back on this as the central event of the entire Middle Ages.

Christian Caesar